The hit Netflix series “Queen’s Gambit” has sparked a recent popular interest in chess, which I think is very cool. But where did the game come from originally? European chess is actually a long-descended derivative of an Indian game which inspired many variants not only among its western neighbors, but among those to the east as well.

Chaturanga was created, at the latest, during the Gupta Empire in the 500s, but it’s possible that it descended from moving-piece games before it. The ancient Greeks who made the land of Baktria their home in the early 200s BCE may have even played a part in Chaturanga’s foundations, but we cannot say for sure.

Unlike the swift-moving bishops and long-ranging rooks of modern Chess, the pieces in Chaturanga generally only moved one square per turn, limited only to which direction that piece was allowed to go. This probably meant longer games, but nonetheless was enjoyable enough to proliferate outside of the Gupta Empire’s immediate sphere of influence.

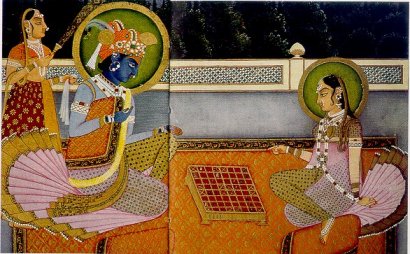

In the original game, the piece which would eventually become the queen was a chief counselor, and the piece which became the bishop was an elephant. While it makes sense that the elephants were transformed into powerful clergy, I have to confess a little sadness that we don’t still get to move elephant-shaped figures around the board, which sounds like fun.

Derivations and Innovations

Chaturanga arrived on the distant shores of Japan sometime in the 700s, having already undergone changes and alterations as it traveled through various regions in China. The modern descendent in Japan is called Shogi, which underwent a most interesting transformation in the 1400s (we think!) in which captured pieces can be played by their capturer anywhere on the board. This means that Shogi endgames are actually more complex than those of Chess, as any second the game could be completely upended by a clever and strategic “drop” of a captured piece.

Some of the pieces can “promote” by being flipped to their red side, which gives them even more options for moves around the board if they reach into the back three ranks of their opponent’s side of the board. Shogi games are very exciting, though the average game takes from 30 minutes to two hours, depending on the players’ relative skill.

In Thailand, Chaturaga was transformed into the game of Makruk, which features similar movements to both European Chess and Chaturanga. The queen, for example, moves only one space diagonally in any direction. However, the equivalents of knights, bishops, and rooks take on the same movement. The pawns, while unable to move two spaces on their first turn, play a critical role in the endgame when they are eliminated from the board.

As soon as the pawns are eliminated for both players, a move countdown begins in which either one player must checkmate the other or the game is automatically declared a draw. How many moves are left in the countdown depends upon how many of the major pieces are left. There are many regional variants to this game, and similar versions are played in neighboring countries.

This brings us to Sittuyin, the Burmese variant which has a very interesting deployment mechanic. The pawns are set up in a staggered position near the center of the board, but then the players arrange their major pieces in any formation they like on their own side. In tournaments, a screen is used to ensure that each player’s opening deployment is kept secret until the game begins.

In addition to the 64 squares of a typical chessboard, Sittuyin also has diagonal lines which are used in promoting pawns. Unlike pawn promotion in chess, through which a player can end up having two or three queens on the board, a pawn in Sittuyin can only promote to a piece which the opponent has already captured.

Transformations and Deviations in Europe

European Chess underwent several metamorphoses in the Middle Ages. The Knight’s jumping movement, for example, was conceived during this time, as was the improved, godlike movement of the Queen’s piece.

By the 1700s, the chess pieces had all adopted the movement which we are familiar with today. Throughout this period, and into the 1800s, the game was primarily enjoyed by those who had time and resources to invest into it: aristocrats, nobles, and the growing class of the bourgeoisie. We even have a few recorded games from Napoleon Bonaparte, though let’s just say his real talent lay on real-life battlefields (No offense, mon général!).

By the mid-1800s, chess sets could be found in every salon and cafe, and it became a universal pasttime of the nobles and commoners alike. Great early players like Morphy and Blackburne became well known for their particular techniques (Morphy for his strategic positional play and Blackburne for his audacious assaults and occasional drunken fist-fights).

Gradually the game evolved, along with society, toward more scientific lines. Great players began writing books describing their strategies, the oldest of which are available free online (check out Capablanca’s or Lasker’s, if you’re so inclined!).

Eventually the computers took it over, as they tend to do. The strongest chess champion today will get brutally shredded by the average chess engine, and I don’t mean that as an insult. It’s not exactly fair play if your opponent is able to calculate the likelihood of checkmate resulting from 2,000 possible moves in the space of a second. Gary Kasparov is famously known as the first Chess World Champion to be defeated by a computer chess engine, but it was going to happen to somebody eventually.

That being said, computer engines continue to help chess theorists develop new strategies based on those programs’ available choices in a given game. Because it’s a two-player game, there’s no one way to play chess that will lead to victory every time, and I think that is why we continue to play it. Even with everything we know about it, the game can still surprise us and something about that is beautiful.